Choosing a Donabe(土鍋) and the Science of Soaking for Grains That Stand Proud

If you asked a Japanese chef, “What is the most difficult dish to make?” many might answer without hesitation: “Plain white rice.”

Sushi and tempura are, of course, profound in their own right. But the quiet foundation beneath nearly every Japanese meal—the one element that gently yet decisively shapes the quality of the entire table—is a single bowl of rice, gohan. Precisely because it is so simple, it allows no shortcuts and no disguise. That is why, at Chagohan Tokyo, we devote our deepest respect and our fullest technique to this most fundamental dish.

Why do we choose a “donabe”?

In modern Japan, most households own highly capable electric rice cookers. In an era when anyone can cook rice at the push of a button, why do we intentionally choose the more demanding path of cooking with a donabe—an earthenware pot?

The answer lies in how a donabe transfers heat. Its thick clay walls slowly absorb heat over the flame, then release it gently and evenly throughout the pot, carrying warmth to each grain of rice. This “kind” heat penetrates the core without damaging the surface, drawing out the rice’s natural sweetness from its starch to the fullest.

A donabe is brought to a vigorous boil over high heat—and even after the flame is turned off, it cools down slowly. This curve of temperature change is precisely what defines each grain’s outline, creating a finish that is glossy on the outside, yet tender and pleasantly chewy within. The small holes that sometimes appear on the surface—often called kani-ana (“crab holes”)—are proof of strong convection: the most reassuring sign that the rice has been cooked beautifully.

A conversation with rice begins with “washing.”

Washing rice is not merely about removing bran or impurities. We think of it as a delicate conversation—gently creating pathways on the surface of each grain so it can absorb water properly.

If you scrub too forcefully, the grains break and the cooked rice turns heavy and mushy. Yet if you are too gentle, absorption will be incomplete. You focus all your attention into your fingertips, listening to the soft sound of grains brushing against one another, changing the water several times as you wash in a steady rhythm. This balance is something only years of practice can truly teach.

The science within a single grain: adjusting soaking time with the seasons

If there is one step that could be called the most essential in cooking excellent rice, it is soaking. The goal is to let water reach the very center of the grain—down to the area known as shinpaku. Neglect this step, and you risk uneven cooking and rice with a stubborn, undercooked core.

And soaking time must be changed precisely with the seasons, because the speed of absorption depends entirely on water temperature. In summer, when water is warm, about 30 minutes is often sufficient. In winter, when the water temperature drops sharply, soaking may take 90 minutes or more.

Each day, we check the day’s air temperature and water temperature, and sometimes even consider the rice variety and its condition—adjusting soaking time down to the minute. This is living knowledge you won’t find in the manual of even the most expensive rice cooker: an invisible science devoted to delivering rice in its finest state.

A ritual of stillness: “steaming” completes the rice

When the crackling sound fades and a toasty aroma begins to rise, it is time to turn off the heat. But this is not the moment to lift the lid in haste. One final stage remains—the quiet ritual called steaming.

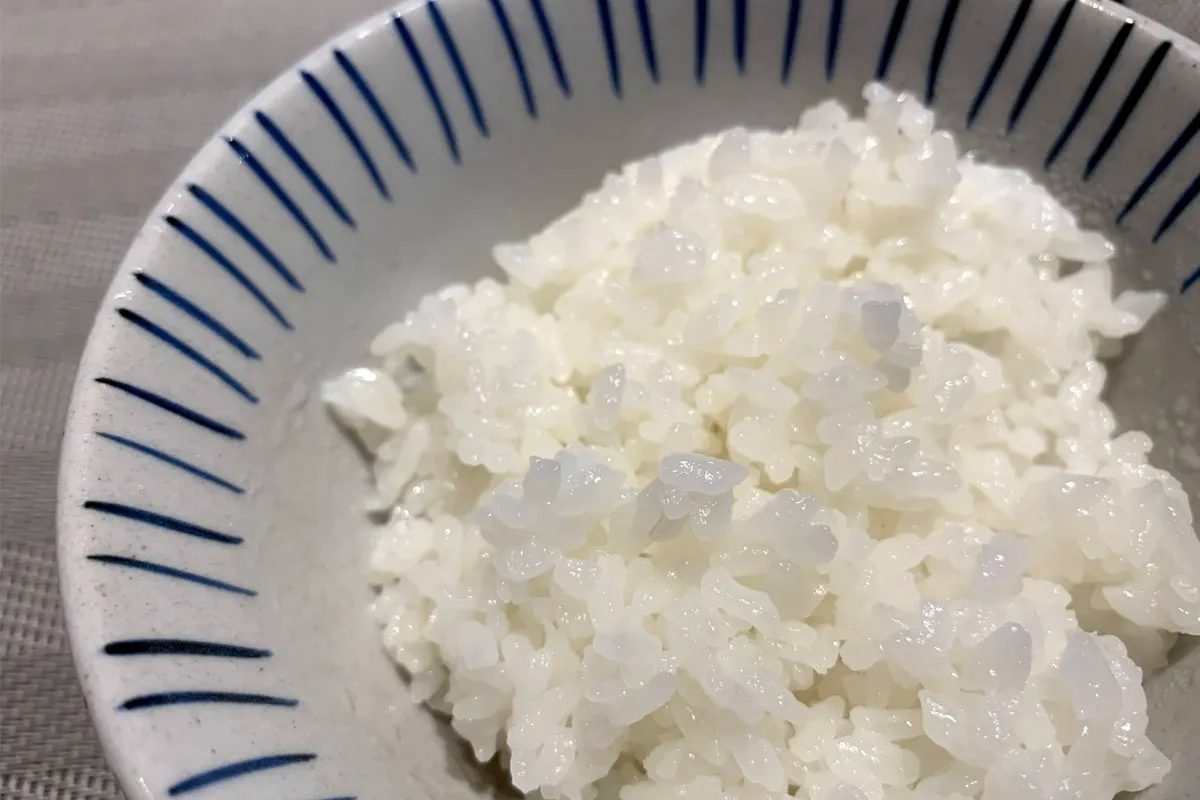

Right after cooking, the grains still carry excess moisture on their surface. By letting the rice steam undisturbed for 10 to 15 minutes, that moisture redistributes evenly inside each grain, creating rice that is fluffy, yet distinct—each grain standing proudly in perfect balance.

Resisting the urge to peek during this silent waiting time is part of the craft. The moment you finally meet the freshly cooked rice is, no matter how many times you experience it, something that feels quietly sacred.

A single bowl of white rice contains our philosophy: deep understanding of tools, a dialogue with nature, and technique backed by scientific insight.

In our Chagohan Tokyo classes, we hope to share not only “how” to cook, but also the Japanese sense of beauty that lives in everyday practice—and the spirit of seeking the essence behind each action. The next time you eat rice, perhaps pause for a moment and imagine the story held within each grain. That single bite may taste different than ever before.

→ View the new classes and prices → View the new Private classes and prices